As Marvel Studios prepares the finale to its decade-long saga with Avengers: Endgame this April, Hollywood’s appetite for shared or expanded universes has only become more ravenous. Many have tried, but few, if any really, have been able to replicate the coveted MCU (Marvel Cinematic Universe) formula.

So maybe that’s why newly christened Academy Award winner, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, feels so refreshing – it constructs an entirely new superhero universe under Sony’s Spider-Man banner without being tied to the continuity of its live-action counterpart.

If that doesn’t sound particularly groundbreaking, it’s important to consider just how much Marvel’s invasion of Hollywood has influenced the way modern audiences engage with movies. In just ten years, studio president Kevin Feige has produced a whopping twenty-one (soon to be twenty-two) films, each crossing over with one another continually building a shared canon with every subsequent installment.

Accordingly, fans have become conditioned to acknowledge and expect a certain level of coherent continuity from Hollywood’s cinematic universes: after Thanos snaps away half of all sentient life in Avengers: Infinity War, that moment not only affects the next Avengers sequel but also every character’s franchise within that world. Think of it as Newton’s third law but for shared universes.

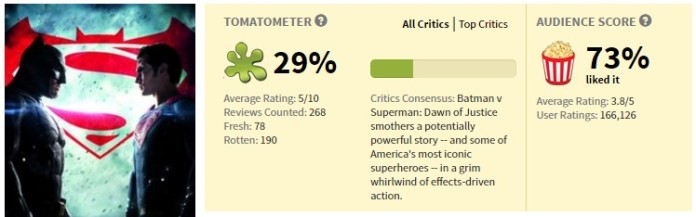

Other studios have tried playing fast and loose with the interconnected-ness of their superhero franchises only to complicate future projects. Fox basically made Days of Future Past to fix their infamously complicated X-Men movie timeline. And then there’s Warner Bros., whose rushed world-building and sloppy imitation of the MCU blueprint derailed their DC cinematic universe for almost five years.

Meanwhile, Sony, whose ownership of Marvel IP extends to roughly 900 characters, most of which are limited to the Spider-Man umbrella, have enjoyed quite a resurgence since partnering with Marvel Studios to co-produce their newest series of Spider-Man films, beginning with 2017’s Spider-Man: Homecoming. Into the Spider-Verse, though, is not one of those films, so the probability for things to turn sideways was actually quite high.

Left to Right: Peni Parker (Kimiko Glenn), Spider-Woman (Hailee Steinfeld), Spider-Ham (John Mulaney), Miles Morales (Shameik Moore), Peter B. Parker (Jake Johnson), Spider-Noir (Nic Cage)

Yes, Into the Spider-Verse is animated, so you could argue that most people wouldn’t think either franchise is related to begin with. But Spider-Verse isn’t just some direct-to-video cartoon greenlit to advertise a toy line. This is a big budget studio undertaking with well-known names like Jake Johnson, Mahershala Ali, and Nic Cage alongside rising stars John Mulaney, Hailee Steinfeld, and Shameik Moore.

If it’s great, everybody wins. If it’s bad, does it hurt public goodwill toward future Spider-Man projects? Sony’s other 2018 Spider-Man spinoff, Venom – which went on to gross just shy of $900M internationally – may indicate the opposite: that poor critical reception actually doesn’t matter.

But even Venom, whose very comic origins and identity are indebted to Spider-Man, was stripped of any references to the web-head as to not complicate Tom Holland’s budding live-action franchise. Or maybe it was to leave the door open for a future crossover?

Since Spider-Verse is effectively a standalone story, though, it isn’t concerned with maybe fitting into someone else’s universe. It can take liberties otherwise discouraged by an already established shared world: like kill off Peter Parker in the first ten minutes.

Don’t worry, this Peter (charmingly voiced by Chris Pine) isn’t really the same Peter that fans have come to know and love. He’s blonde, in perfect shape, and at the peak of his superhero career with little worry in sight – a stark contrast to the blue collar, “every man” persona typically associated with the character.

What stays the same, though, is this Peter’s willingness to sacrifice his life to save other people. And that deeply affects Miles Morales – the true heart of Into the Spider-Verse and star of Marvel’s now-defunct Ultimate Spider-Man comic book series.

Debuting in 2011, Miles has earned a permanent place in the Marvel Comics mythos, but when it comes to live-action appearances, the character has been non-existent from any previous Spider-Man or MCU films.

And it makes sense: Miles only recently came into popularity this decade and Tom Holland just donned the red-and-blue tights back in 2016. But with the freedom of being unbound to any fixed continuity, Sony was able to bring an iconic character like Miles to the forefront of Into the Spider-Verse without waiting years for his live-action MCU debut.

When we first meet Miles in Spider-Verse, he isn’t a superhero yet. So when a radioactive spider inevitably bites him, imbuing Miles with the classic Spider-Man powers – plus a few new tricks – he’s desperate for a mentor. Bad news: the Peter of his universe is dead.

Good news: the multiverse exists and with it, infinite Spider-folk across alternate dimensions who can teach him what it means to be a hero. Six eventually arrive including washed-up Peter B. Parker, Spider-Woman aka Gwen Stacey of Earth 65, 11-year old Peni Parker and her psychic-linked mech “SP//dr” along with cult favorites, Spider-Man Noir and Spider-Ham.

Now you may be thinking “I don’t know what any of that means,” and that’s okay. Comics are notoriously convoluted, and at any given time, you’ll likely find at least two or more versions of the same superhero running around in different books – some adhering to the continuity of its main universe, others not so much.

Under the “Elseworlds” comic imprint, DC has imagined radical interpretations of its most iconic characters like a Superman who was raised in the Soviet Union instead of Smallville or a 19th century Batman hunting Jack the Ripper in Gotham City. The closest analog for Marvel would be their anthology series “What If?” which tells one-off, alternate reality tales ranging from “What if Venom bonded with the Punisher” to “What if Gwen Stacey never died?”

While the actual ‘Spider-Verse’ comic event from 2014 existed within Marvel’s primary “Earth-616” universe, Into the Spider-Verse, the movie, more closely resembles an “Elseworlds” or “What If?” in its approximation to and relationship with Sony’s primary cinematic universe. There are now two majorly successful Spider-Man movie franchises, which begs the question: maybe audiences aren’t as sensitive to new franchises as previously thought?

Credit: Comic Book Resources

Even if they’re not an avid comic book reader, the average superhero moviegoer has probably been at this thing for a decade, if not more. Collectively, we are fully indoctrinated into this pop culture movement and understand its cinematic rules in kind. We’ve been taught how to watch a superhero movie.

The shared universe concept is no longer a groundbreaking idea, and what ultimately puts people in theaters and keeps them coming back are strong, relatable characters.

Into the Spider-Verse above all else understands that without a strong emotional foundation for its characters to draw from, it doesn’t matter if you have one Spider-Man or one hundred. When Miles stumbles over the lyrics of his favorite song – Post Malone and Swae Lee’s “Sunflower” – we all know what that feels like. Or when Gwen Stacey explains how she lost the Peter of her world – subverting her own iconic comic death – we feel that too. It’s loss and love and humor and doubt. And that is Spider-Man. It’s also us, too.

Forget the humanoid pig and hypnotic animation for a second, this is the lesson that Spider-Verse wants us to learn: we’re all Spider-Man. It doesn’t matter who you are – you’re powerful. While nice on paper, that idea can often become muddled by the type of actor that’s historically led a superhero franchise.

No one’s trying to make you feel bad for crushing on Chris Hemsworth or Brie Larson, but when a film like Into the Spider-Verse comes along and embraces new ethnicities, sexes, and nationalities to join this collective mythology, that’s important. Still, we don’t get there without studios actively seeking and embracing new stories that extend beyond the myopic scope of setting up endless crossovers or “phases.”

With a sequel and spinoff already in development, Spider-Verse will inevitably be subsumed into its own shared world of interconnected movies. And that was always going to happen once Sony had even an inkling that this was going to be a hit. Cinematic universes are not inherently evil but rather the uniformity and sterility that they engender. Let Into the Spider–Verse, then, shine bright as a beacon for what’s possible when you break from the mold.